Giant data centers in orbit: an environmental record far from the promises

They are presented as cleaner than terrestrial data centers. Yet, available data paints a damning picture.

In recent months, spectacular statements and announcements regarding the deployment of orbital data centers have multiplied, with one argument repeated ad nauseam: they would be far more environmentally virtuous than their terrestrial counterparts.

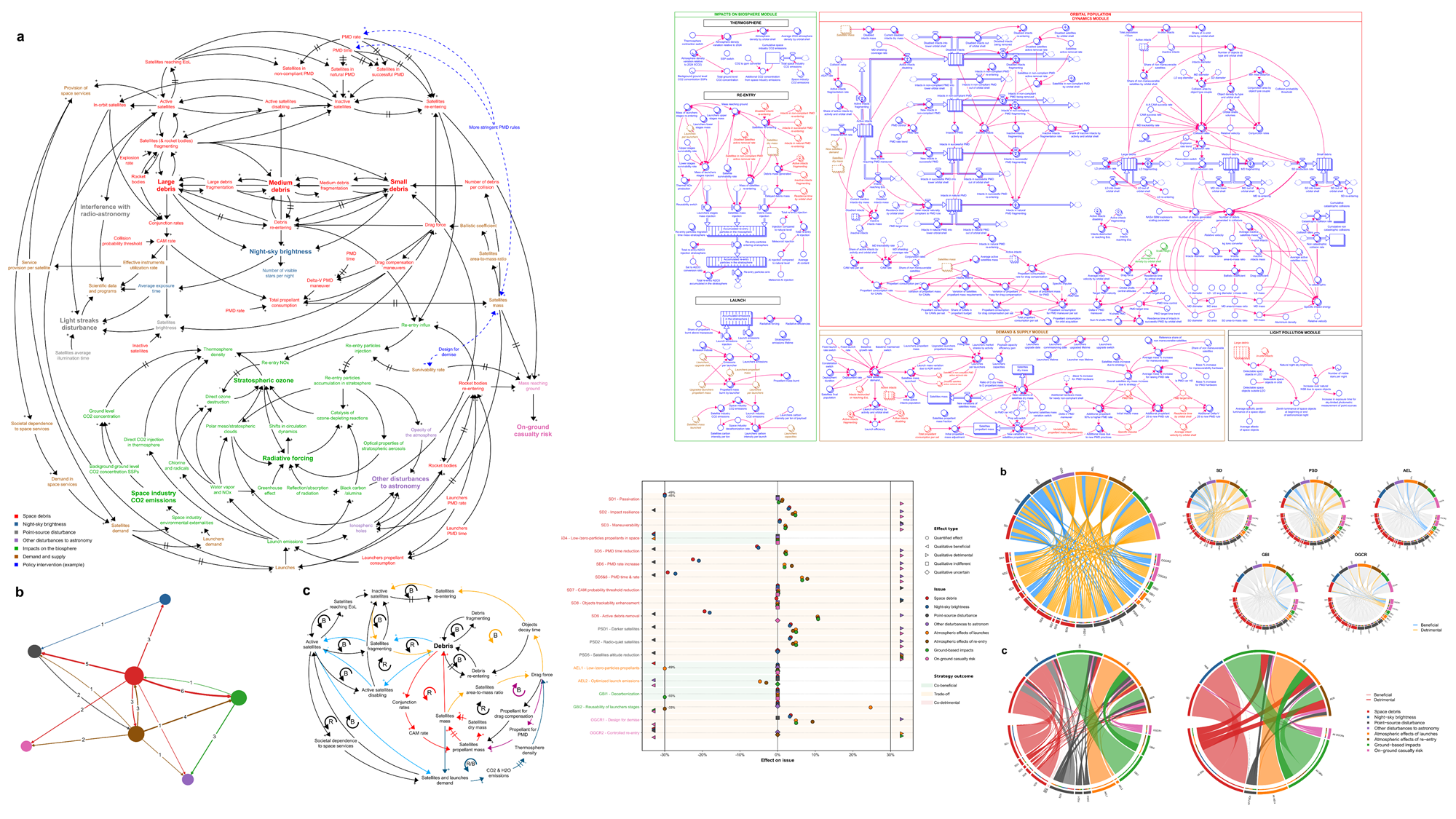

Faced with these unfounded claims, almost always made without contradiction, this article aims to re-anchor the discussion in scientific reality, drawing on the existing state of knowledge concerning the life-cycle impacts of space systems, the effects of launches and re-entries on the atmosphere, the risks of ground fallout and space debris, and the disruption of astronomical observations.

I will not address the technical and economic aspects, which have been analyzed elsewhere by individuals far more competent than myself on these subjects.

NB: most of what is presented here also remains valid for any other large-scale infrastructure project in space.

Before diving into the heart of the matter, here are some elements of context.

Context

An avalanche of announcements

To set the stage, here is a non-exhaustive summary of recent news regarding Space Data Centers (SDC) over the last few months:

- Last October, Jeff Bezos claimed that gigawatt-scale SDCs could be deployed within two decades1.

- Shortly after, Elon Musk stated that SpaceX would also “do data centers in space,” and in late January, the company merged with xAI and filed an application to deploy one million satellites in low Earth orbit (for reference, there are currently 15,000 satellites in orbit, including about 10,000 Starlinks deployed by SpaceX since 2019, already representing a massive shift from the ~2,000 total satellites present before that date).

- According to the Wall Street Journal, OpenAI CEO Sam Altman recently approached the American company Stoke Space to explore a launch method competing with SpaceX.

- The startup Starcloud, incubated by Nvidia, has placed its first satellite in orbit carrying an NVIDIA H100 GPU, presented as a demonstrator, and announces a target of a 5 GW data center by 2035, which would require solar panels on a square 4 km per side. Its CEO, Philip Johnston, does not hide his ambitions: according to him, the dominance of SDCs over their terrestrial equivalents is inevitable and effective within a decade; there would be “no debate”2,3.

- In early November, Google in turn announced its intention to deploy SDCs dedicated to AI as early as 2027, followed by a constellation of 81 objects orbiting in formation, detailing the concept in a preprint publication4.

Interest in these AI-powering SDCs is not limited to American private actors:

- In early 2025, China launched the first of a constellation of 2,800 satellites with this objective5.

- In late November, just days before the European space budget vote, the European Space Policy Institute published a report strongly calling on Europe to commit to this path, citing the risk of a decisive lag in a technology perceived as disruptive and strategic6.

- Europe had already explored the idea with the ASCEND study led by Thales Alenia Space for the European Commission in 2023/20247 – we will return to this.

As seen in these announcements, SDCs can take different shapes and sizes depending on taste and ambition. But, why do it?

Data centers facing terrestrial limits

These recent announcements and statements occur in a well-identified context: rapid growth in the electricity consumption of Terrestrial Data Centers (TDC), with AI being one of the main drivers. According to the International Energy Agency, it accounts for 1.5% of global consumption and is expected to more than double by 2030 in its reference scenario8. In the United States, its growth is particularly marked: it could represent about 10% of national consumption by that horizon.

This dynamic exerts major pressure on the development, planning, decarbonization, and stability of power grids9,10. Added to these physical constraints are social and institutional barriers: local opposition to the installation of new centers, conflicts of use over water and electricity, difficulties in obtaining permits, and grid interconnection delays3,11.

In parallel, on the economic and financial level, the existence of a speculative bubble around AI is now widely discussed. For its part, the private space sector is accustomed to operating on an economy of promise, and its champion SpaceX greatly needed to renew a narrative of Mars conquest that was losing momentum as its IPO approached.

In this context, the timing was ideal to dangle a perfect solution.

A supposed ecological interest as a central justification

In orbit, data centers would theoretically benefit from continuous access to solar energy and thermal management free from water consumption, while the reduction in space access costs would make this model economically viable. SDCs are then presented as the inevitable next step in AI development, allowing for the circumvention of the terrestrial constraints discussed previously.

However, while the technical and economic dimensions of these projects have been widely analyzed and criticized, the question of ecological sustainability has hardly been addressed. Yet, it is central to the very justification of their existence and is systematically taken for granted without any factual evidence being provided to support it. No surprise here: NewSpace is accustomed to this12.

To cite one example among many: in an article published on the World Economic Forum website titled “How Data Centres in Space Sustainably Enable the AI Age”, the CEO of Starcloud asserts that SDCs would allow for “a massive reduction in environmental impact”13.

What is the reality?

Even on a scope favorable to SDCs, it’s 1-0 for TDCs

The architecture of an SDC differs from that of a TDC, notably with components that must withstand space environment conditions (vacuum, radiation, extreme thermal constraints, etc.) and a radically different cooling system. These conceptual differences will naturally affect the associated environmental impacts over the respective life cycles of SDCs and TDCs. Let’s focus here on the most obvious difference that plays a central role in the environmental record: an SDC requires space launchers to be deployed in orbit.

Emissions over a rocket’s life cycle before launch

For a rocket to be placed on its launch pad, ready for liftoff, it had to be designed, manufactured (using advanced materials and industrial processes), its components transported and assembled, its fuels and oxidizers produced and stored, and in the case of rockets with reusable parts, components recovered, refurbished, and possibly replaced after landing. Additionally, numerous infrastructures must be built, operated, and maintained (factories, launch pads, control centers, etc.).

The few available studies, focusing on Ariane 5 and 6 rockets, estimate the greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions related to these pre-launch phases at between 20,000 and 30,000 tonnes of CO2 equivalent. Since their capacity is about twenty tonnes of payload in low Earth orbit, this corresponds to several thousand tonnes of CO2 per tonne of payload-an order of magnitude also valid for other launchers.

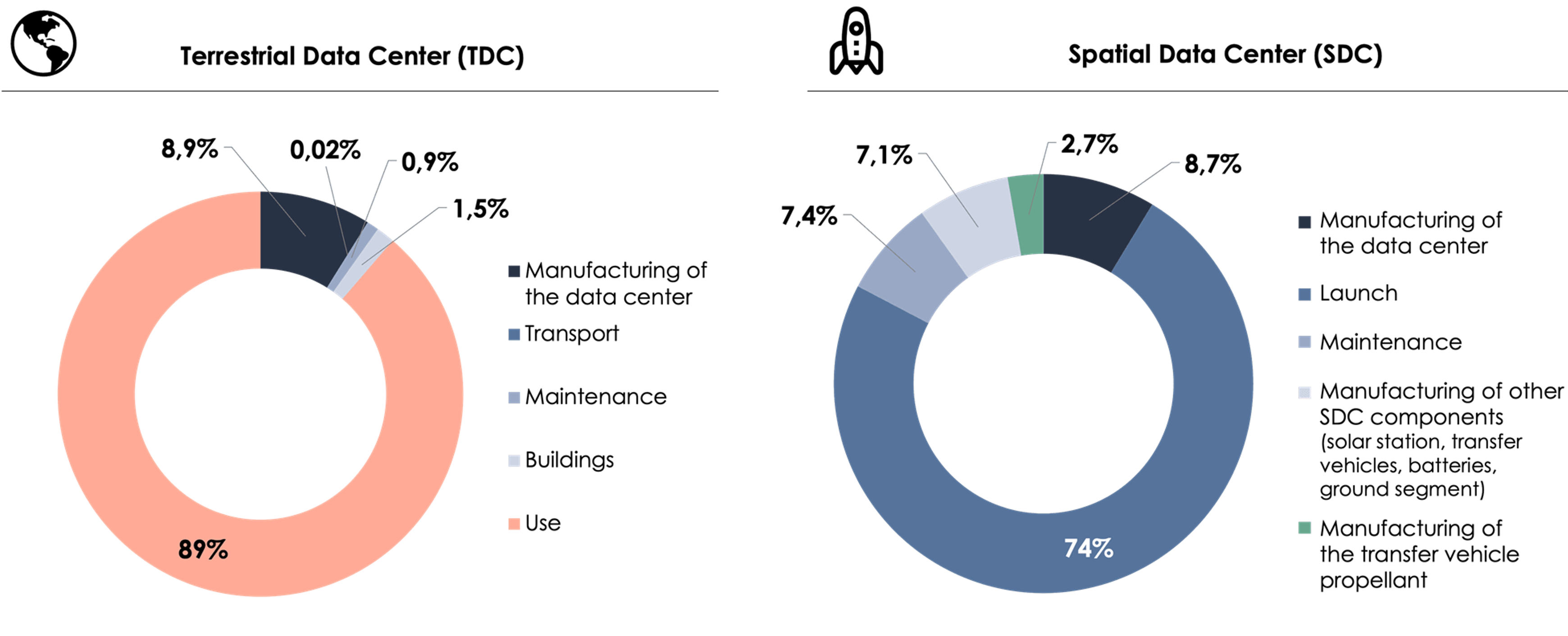

Space vs Terrestrial Data Center: the comparative record

The impact of these additional life stages compared to a TDC is major. The European study ASCEND7 attempted to evaluate the climatic benefit of an SDC by comparing its GHG emissions to those of a TDC while taking these life stages into account. It is, notably, the only study to have done so.

Result:

data centers in space become more interesting than terrestrial data centers if and only if the launcher can be reusable and that it emits less than 370 kgCO2/kg of payload [0.370 tCO2/t] on average over its entire lifespan.

In other words, current launchers are far too polluting for SDCs to be advantageous. One of the consulting firms involved in the study explicitly summarizes the scale of the challenge: for SDCs to offer a benefit over TDCs, it would be necessary to “divide by 10” the carbon intensity per kg of payload, which would constitute “a true feat”14.

This clear and quantified (though uncertain) element is completely absent from technical critiques and debates. It is sometimes even contradicted by the study’s own managers in interviews-or let’s say, to give them the benefit of the doubt, “interpreted in an extremely optimistic manner”15:

We can say today that the results are very encouraging,

We have found a solution that is technically feasible, makes financial sense and has a less impactful carbon footprint than on Earth

The record presented here is therefore already unfavorable to SDCs. Yet, it does not yet take into account what is arguably the most critical environmental issue for space infrastructure: the effect of launches and atmospheric re-entries.

At liftoff, the real trouble begins

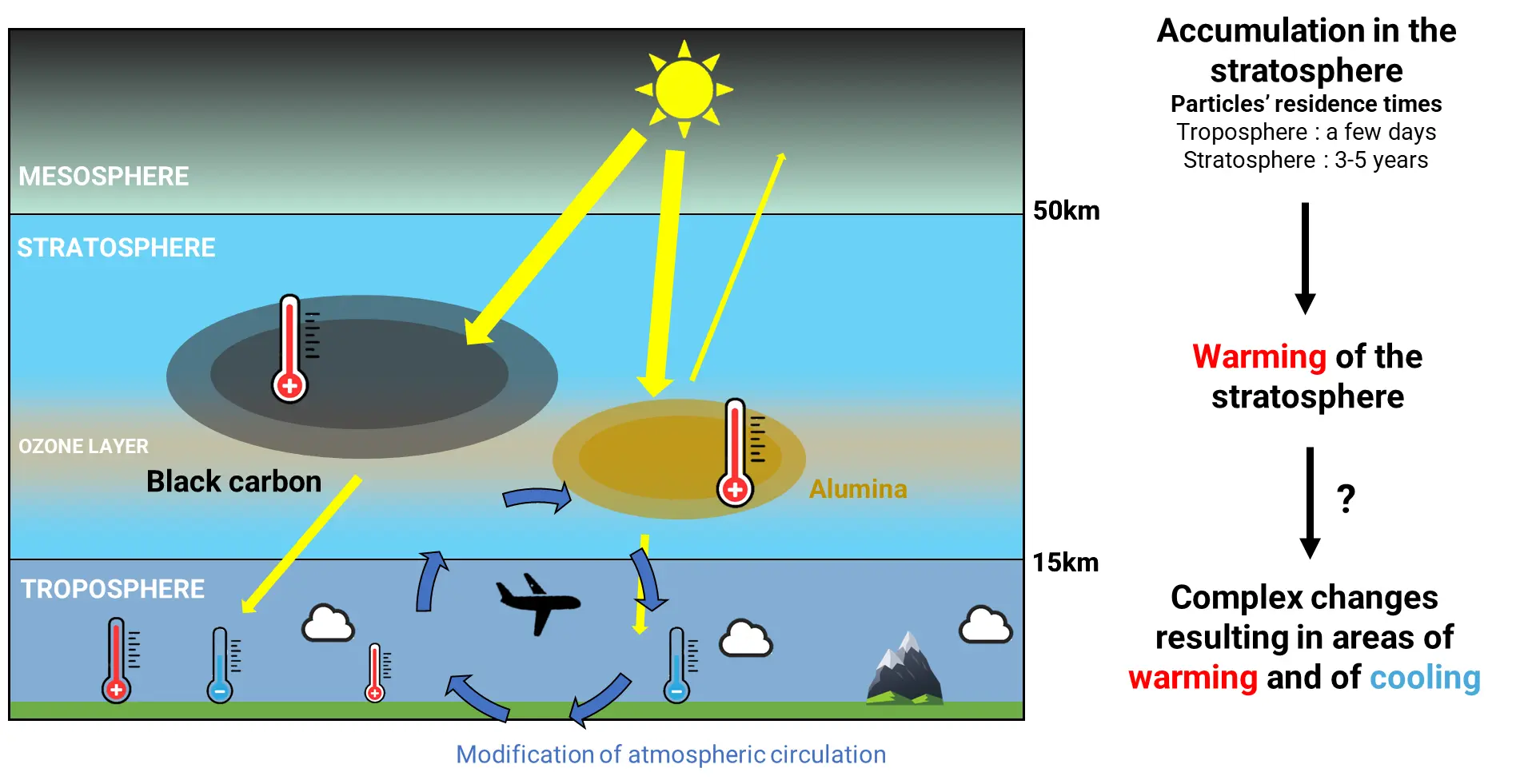

Numerous and persistent particles

The climatic impact of space launches is very specific for several reasons.

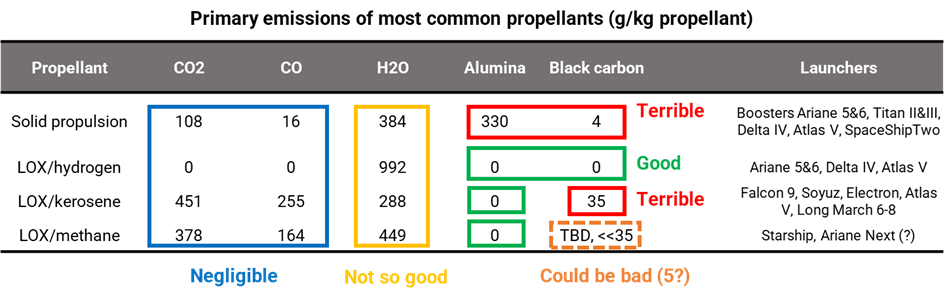

First, a rocket engine does not only release GHGs (CO2, H2O), but also particles (soot, alumina) in very large quantities, which prove to be more problematic. In the extreme case of an open-cycle kerosene engine, soot emissions can be up to 1,000 times higher than those of an aircraft engine per kg of fuel burned16.

Furthermore, unlike other human activities whose emissions remain largely confined to the lowest layer of the atmosphere - the troposphere - rockets emit these compounds throughout their ascent from the ground to orbit, particularly in the stratosphere (~10-50 km).

At these altitudes, these compounds are more persistent. For example, in the troposphere, particles are removed in a few days by air circulation and rain, but in the stratosphere, their lifespan is several years. They therefore have much more time to disrupt the atmosphere’s radiative balance by absorbing and/or scattering incoming solar radiation and outgoing infrared radiation.

Their impact there is thus decupled: it is estimated, for example, that a soot particle emitted by a rocket in the stratosphere has a warming potential ~500 times higher than the same particle emitted at ground level. Because of these effects, climate model results show that rocket emissions cause warming of the stratosphere.

Complex and poorly understood effects

While this warming of the stratosphere is scientifically established17,18,19, the complete response of the climate system remains poorly understood. It could induce complex changes in ozone chemistry, atmospheric circulation, temperature distribution, and aerosol optical properties, etc., which are not yet fully integrated into current climate simulations. Available studies therefore remain cautious about the final effect at ground level, mentioning the possibility of regional warming and cooling zones17.

Added to these radiative effects are impacts on the ozone layer, via several mechanisms (direct emissions of ozone-depleting compounds, indirect effects via stratospheric warming, providing reactive surfaces).

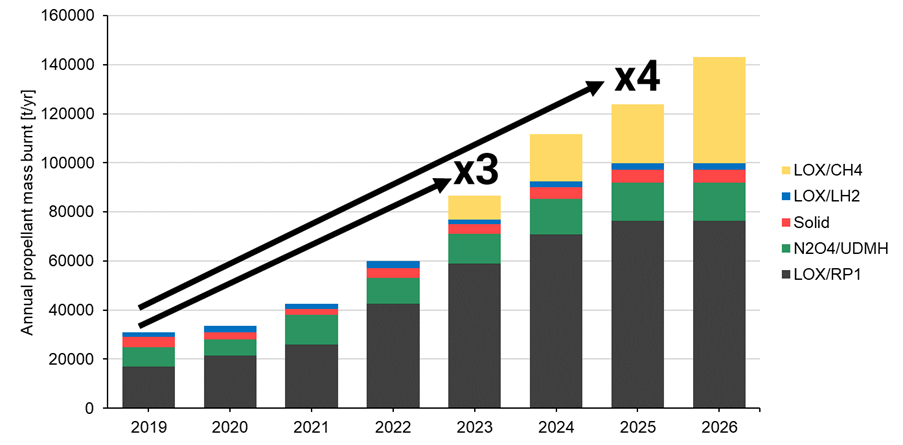

SDCs would add to a growing pressure on the upper atmosphere

The deployment of massive infrastructures like the announced SDCs would involve numerous and frequent launches, sometimes drastically more depending on their size. According to the CEO of Starcloud, the lifespan of these systems would be around 5 years3, implying the regular repetition of deployment operations and, with them, the associated emissions.

In a context where the space sector is already experiencing rapid growth, this multiplication of launches raises serious concerns. Indeed, the most recent models suggest that if cumulative emissions from launchers continue to increase at this rate, they could slow down or even delay the recovery of the ozone layer made possible by the Montreal Protocol19,20. Another study estimates that a scenario involving soot injections 10 times higher than current levels would lead to a stratospheric temperature rise of about 1.5°C17.

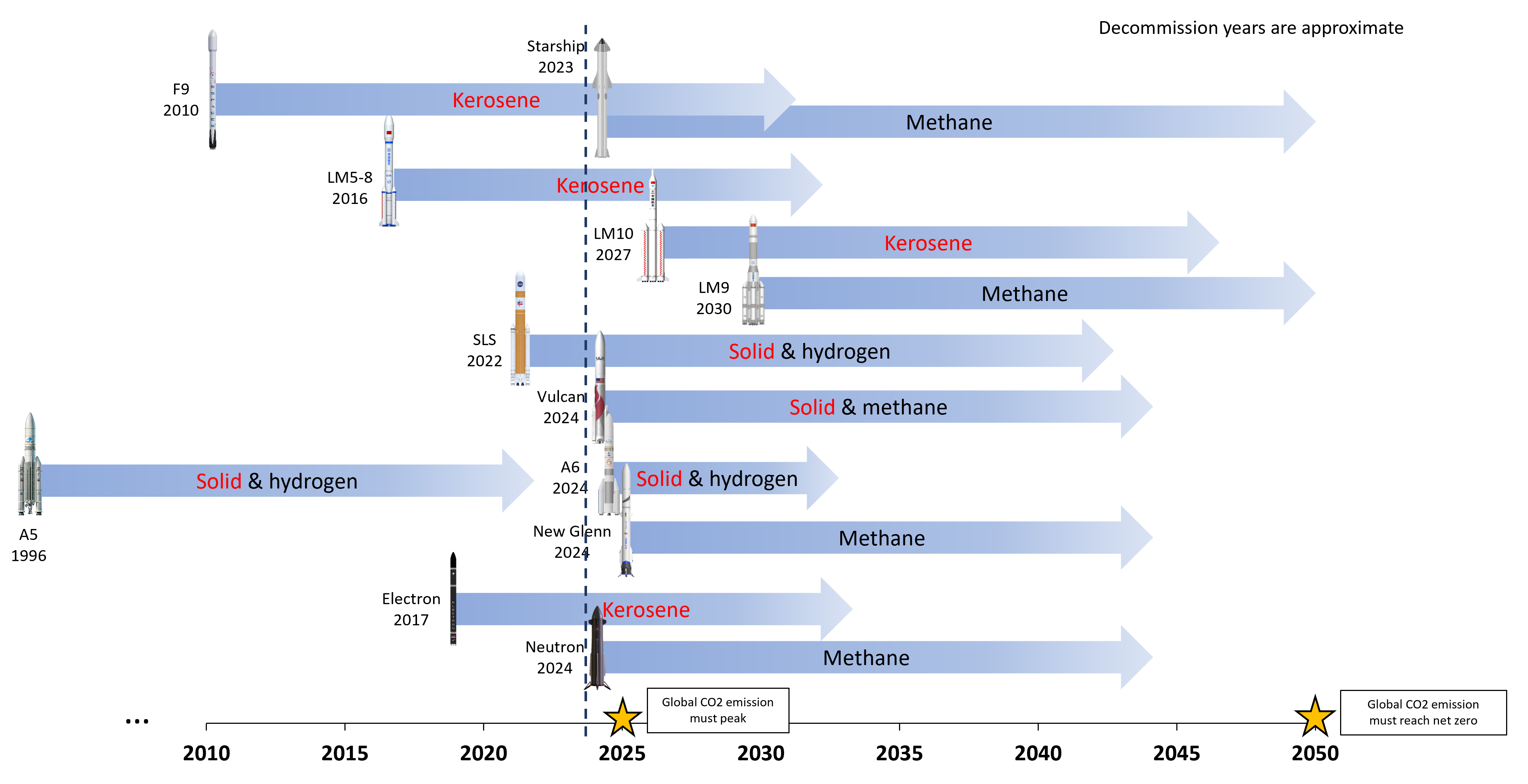

The contribution of SDC projects to these problems would highly depend on the type of fuel used by the launchers for deployment, which could be more or less emissive of particles and ozone-depleting substances. However, even if significant improvements are theoretically possible, no fuel will totally eliminate these problems, and in practice, a rapid and massive transition to “cleaner” fuels is hardly credible.

These effects of launches on climate and ozone are ignored in classic life-cycle analysis studies, such as the one conducted by ASCEND, because taking them into account requires the use of complex climate simulations. They therefore further darken an already unfavorable record for SDCs. Yet, the picture remains incomplete: during their return to the atmosphere, satellites and rocket stages could also have effects, which are largely unknown to this day.

Re-entry: the great unknown

SDCs are generally envisioned for low Earth orbits (LEO). Like all satellites and rocket stages operating in this region, they must be actively or naturally de-orbited at the end of their operational life.

Metallic particles and the ozone layer

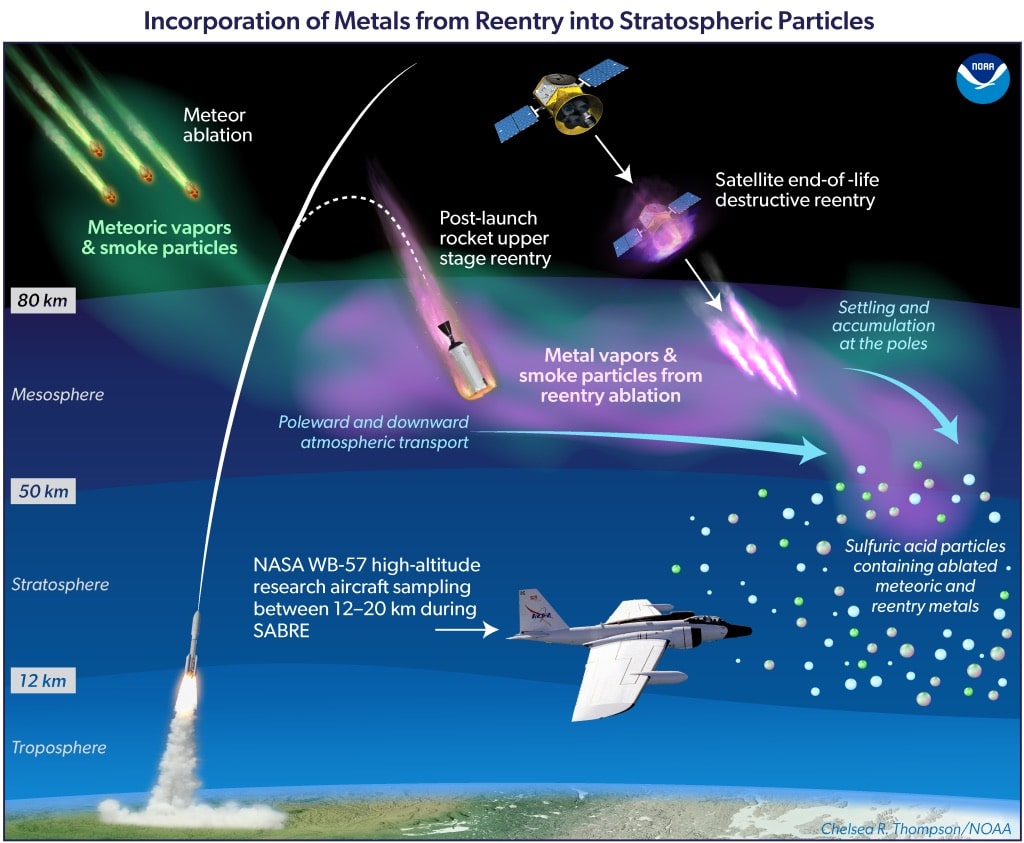

During atmospheric re-entry, these structures partially or totally burn up and release metallic particles into the mesosphere (~50-85 km). These particles condense, aggregate with other existing aerosols, and slowly descend toward the stratosphere, where the ozone layer is located.

A study21 published in 2023 by the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA), an institution that Musk and the DOGE have attacked for “harming U.S. prosperity”, detected particles from space systems in 10% of the analyzed stratospheric aerosols. This result indicates that emissions linked to the return of space systems are no longer marginal and that they affect the physicochemical behavior of a significant fraction of stratospheric aerosols. The authors remain cautious regarding conclusions but discuss several possible effects on the climate and the ozone layer.

Another study22 also warns of a delayed effect, as these particles could potentially take decades to descend into the stratosphere and contribute to ozone destruction processes. In other words, the potential impacts could manifest long after the massive deployment phase, at a time when it will be difficult to avoid the return and ablation of SDCs in the atmosphere, or when a large quantity of particles will already be on their way.

Victims at impact?

Beyond atmospheric impacts, the return of space systems also poses direct risks to human life. Some structural fragments survive re-entry and reach the ground, a phenomenon generally controlled for satellites or rocket stages, but particularly concerning for large-scale infrastructures (or those made of a very large number of objects). For example, a recent NASA study estimated that the re-entry of the Hubble Space Telescope, which is much smaller than some envisioned SDCs, had an average probability of causing a casualty of 1/33023. The multiplication of uncontrolled re-entries also poses increasing air safety issues, with more frequent airspace closures24.

Space Debris: high vulnerability, high danger

The probability of a collision for an object in orbit depends directly on its surface area. The giant infrastructures envisioned for some SDCs would therefore be particularly vulnerable, having an exposed surface area to debris flow far beyond that of conventional satellites.

In the event of a major collision or service failure (breakdown, cyberattack), such an infrastructure could generate a massive amount of additional debris. Limiting these risks would require specific protection and mitigation measures: shielding, advanced detection and warning capabilities, and sufficient maneuverability to perform collision avoidance (onboard propulsion systems, refueling operations). All of these are costly in terms of mass, increasing launch/re-entry needs and thus weighing down the environmental record.

Is this credible? To date, there is, to my knowledge, no space debris study specifically dedicated to these SDCs. However, work exists on a neighboring concept: orbital solar power stations. A recent NASA study emphasizes that such structures would likely lack both sufficiently high-performance warning systems and the maneuverability required to effectively avoid collisions, identifying orbital safety as a major hurdle25.

In a context where the orbital environment is becoming increasingly risky, particularly in LEO with the proliferation of constellations, adding massive and vulnerable structures would be a very risky gamble.

A distributed architecture relying on a large number of satellites rather than a single giant structure would only gain in maneuverability, while introducing other constraints: managing formation flight, multiplication of propulsion systems, and lack of equipment sharing, thus likely increasing deployed surface area, total mass, and associated impacts.

Astronomical observations: one more burden

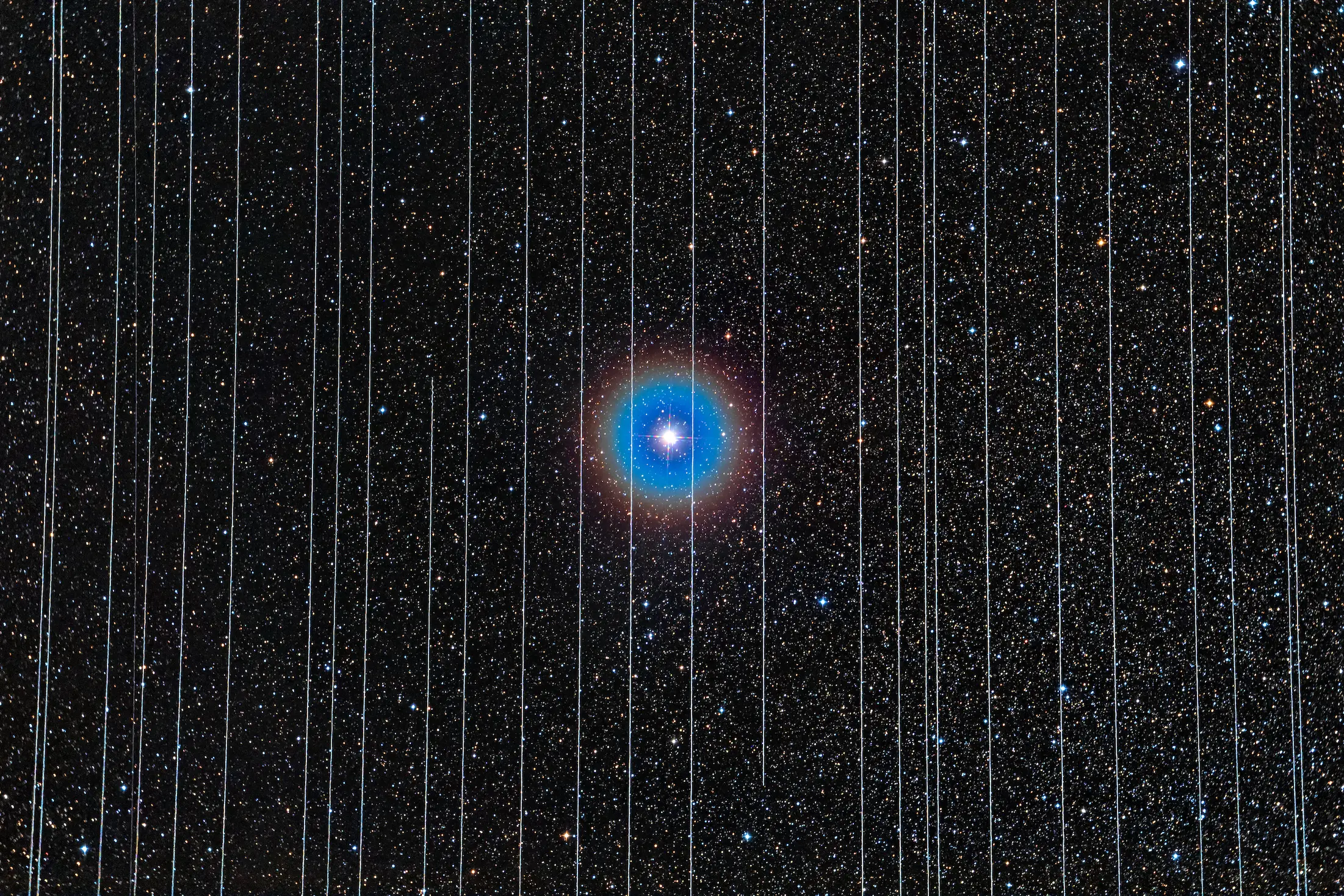

Satellites and debris in orbit already pose major problems for astronomy: light trails contaminating optical astronomy images and creating false alerts, disruption of radio astronomy due to active communications and unintentional electromagnetic emissions from onboard electronics, increase in the diffuse brightness of the night sky, etc.

Several proposals for massive orbital structures, sometimes specifically designed to reflect sunlight, have already raised strong concerns within the astronomical community.

Regarding SDCs, once again, no study dedicated to their impact on astronomy exists to date. According to the CEO of Starcloud, these infrastructures placed in Sun-synchronous orbit would be visible at dawn and dusk, appearing as objects spanning “nearly a quarter of the width of the Moon,” thus constituting a major change for the night sky during these periods3.

While the majority of observations are performed outside these periods during the astronomical night, some critical observations rely precisely on these windows. This is the case for the detection and tracking of Near-Earth Asteroids, as highlighted by astronomer Samantha Lawler in an interview with Scientific American11. For radio astronomy, where observations occur day and night, it is unknown how ground communications and unintentional leaks from onboard electronics might introduce disturbances.

Finally, as mentioned earlier, the deployment of large orbital structures could worsen the space debris problem. Accidental fragmentation or progressive degradation of such infrastructures would increase the number of uncontrolled and potentially reflective objects in orbit, contributing in the long term to a problematic rise in diffuse night sky brightness26,27.

Can innovation save the record?

Are there credible solutions available to eliminate, or at least drastically reduce, the issues discussed, making SDCs a truly more sustainable solution than TDCs?

At this stage, the prospects appear very limited.

In an accelerationist context: no substitution, but capacity stacking

Even assuming that SDCs were indeed more environmentally virtuous than TDCs - a hypothesis largely refuted by the evidence presented in this article - it is essential not to confuse environmental efficiency improvements with absolute impact reduction. A potential climatic benefit from SDCs can only exist in a scenario of strict substitution for TDCs, and not in a logic of stacking or global expansion of capacities.

However, the announcements and discourse from tech giants clearly align with the opposite dynamic, marked by an accelerationist ideology. This posits that AI development must be accelerated, freed from all constraints (ethical, legal, environmental, etc.), to lead as quickly as possible to a radical transformation of society and the resolution of humanity’s great problems. This vision belongs to a broader conception of technological progress as salvation, diverting attention from the very real damage (environmental, but also social) it causes here and now by relying on distant and abstract scenarios presenting utopian futures35.

Within this framework, the impacts described throughout this article are considered unimportant, on the grounds that AI will eventually solve everything. Sam Altman, CEO of OpenAI, thus claims that accelerating AI capabilities would open an “Intelligence Age” characterized by unimaginable prosperity and “staggering triumphs,” going as far as to “fix climate change”36,37. In this logic, it is not at all about replacing TDCs with a supposedly more virtuous alternative. It is about deploying all options simultaneously, terrestrial and space-based, whether SDCs are more sustainable than TDCs or not.

It is worth distinguishing these dynamics from European projects, which generally do not follow the same logic. ASCEND is not Starcloud or Suncatcher, just as IRIS2 is not Starlink or Amazon Leo. As with IRIS2, the intention may be to develop these technologies for economic and strategic reasons - though the relevance of SDCs in this sense remains largely to be proven - and lead to environmental trade-offs. But these compromises must then be acknowledged, made explicit, and debated as such, rather than being presented as ecological progress when all available data points in the opposite direction.

Conclusion

SDCs are presented as the next inevitable step in AI development, allowing for the circumvention of terrestrial social and physical constraints despite immense technical challenges, and drastically reducing environmental impacts despite a total lack of evidence.

Scientific evidence available shows, on the contrary, that they likely significantly increase GHG emissions compared to TDCs, while introducing major new risks for the upper atmosphere, Earth orbit, and the night sky. There is no indication that these problems could be resolved in the short or medium term.

References

1. Pollina, E. & Piovaccari, G. Data centres in space? Jeff Bezos says it’s possible. Reuters (2025).

2. “In ten years, most new data centers will be built in space.” Les Echos Link (2025).

3. Tan, E., Francisco, R. M. T. & Angeles, R. M. Even the Sky May Not Be the Limit for A.I. Data Centers. The New York Times (2026).

4. Arcas, B. A. y et al. Towards a future space-based, highly scalable AI infrastructure system design. Preprint DOI: 10.48550/arXiv.2511.19468 (2025).

5. Jones, A. China launches first of 2,800 satellites for AI space computing constellation. SpaceNews Link (2025).

6. Data centres in space: orbital backbone of the second digital era? ESPI Link.

7. Testimonies | ASCEND. Link.

8. Energy demand from AI – Energy and AI – Analysis. IEA Link.

9. Chen, X., Wang, X., Colacelli, A., Lee, M. & Xie, L. Electricity Demand and Grid Impacts of AI Data Centers: Challenges and Prospects. Preprint DOI: 10.48550/arXiv.2509.07218 (2025).

10. Page, D. R. AI could keep us dependent on natural gas for decades to come. MIT Technology Review Link.

11. Hsu, J. Space-Based Data Centers Could Power AI with Solar Energy-At a Cost. Scientific American Link.

12. Di Tullio, P. & Rea, M. A. The dark side of the new space economy: Insights from the sustainability reporting practices of government space agencies and private space companies. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 31, 4651–4672 (2024).

13. How data centres in space sustainably enable the AI age. World Economic Forum Link (2026).

14. Carbone 4. Are data centers in space a lever to decarbonize the digital sector? Link.

15. Why Europe is looking into sending data centres into space. Euronews Link.

16. What is the environmental impact of a supercharged space industry? The Space Review Link.

17. Maloney, C. M., Portmann, R. W., Ross, M. N. & Rosenlof, K. H. The Climate and Ozone Impacts of Black Carbon Emissions From Global Rocket Launches. J. Geophys. Res. Atmospheres 127, e2021JD036373 (2022).

18. Ross, M. N. & Sheaffer, P. M. Radiative forcing caused by rocket engine emissions. Earths Future 2, 177–196 (2014).

19. Ryan, R. G., Marais, E. A., Balhatchet, C. J. & Eastham, S. D. Impact of Rocket Launch and Space Debris Air Pollutant Emissions on Stratospheric Ozone and Global Climate. Earths Future 10, e2021EF002612 (2022).

20. Revell, L. E. et al. Near-future rocket launches could slow ozone recovery. Npj Clim. Atmospheric Sci. 8, 212 (2025).

21. Murphy, D. M. et al. Metals from spacecraft reentry in stratospheric aerosol particles. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 120, e2313374120 (2023).

22. Ferreira, J. P., Huang, Z., Nomura, K. & Wang, J. Potential Ozone Depletion From Satellite Demise During Atmospheric Reentry in the Era of Mega-Constellations. Geophys. Res. Lett. 51, e2024GL109280 (2024).

23. Koehler, H. M. et al. Hubble Space Telescope and Swift Observatory Orbit Decay Study. (2025).

24. Wright, E., Boley, A. & Byers, M. Airspace closures due to reentering space objects. Sci. Rep. 15, 2966 (2025).

25. Rodgers, E. et al. Space Based Solar Power. (NASA Study).

26. Barentine, J. C. et al. Aggregate Effects of Proliferating LEO Objects and Implications for Astronomical Data Lost in the Noise. Preprint DOI: 10.48550/arXiv.2302.00769 (2023).

27. Kocifaj, M., Kundracik, F., Barentine, J. C. & Bará, S. The proliferation of space objects is a rapidly increasing source of artificial night sky brightness. Mon. Not. R. Astron. Soc. Lett. 504, L40–L44 (2021).

28. Miraux, L. Earth-Space Sustainability Dynamics. ESS Open Arch DOI: 10.22541/essoar.175682860.02417020/v1 (2025).

29. Miraux, L., Pineau, L. & Noir, P. Parametric Life Cycle Assessment of a Space Launch Service Based on a LOx/Biomethane Semi-reusable Launcher. 73rd International Astronautical Congress (Paris, 2022).

30. Gatti, E. ESA and ClearSpace announce PRELUDE mission to test debris-removal techniques. SpaceNews Link (2026).

31. SpaceX. Brightness Mitigation Best Practices for Satellite Operators. PDF (2022).

32. Boley, A. C., Green, R., Rawls, M. L. & Eggl, S. IAU CPS Satellite Optical Brightness Recommendation: Rationale. Res. Notes AAS 9, 60 (2025).

33. Mallama, A. et al. Assessment of Brightness Mitigation Practices for Starlink Satellites. Preprint arXiv:2309.14152 (2023).

34. Mallama, A., Cole, R. E., Harrington, S. & Respler, J. Brightness Characterization for Starlink Direct-to-Cell Satellites. Preprint DOI: 10.48550/arXiv.2407.03092 (2024).

35. Okolo, C. T. The paradox of AI accelerationism and the promise of public interest AI. Science 390, eaeb5789 (2025).

36. Page, J. T. Sorry, AI won’t “fix” climate change. MIT Technology Review Link.

37. The Intelligence Age. Sam Altman Blog Link (2024).