Are we going to lose astronomy and astrophysics?

Overview of the impact of space activities on astronomy and reflection on astronomers' defense strategies.

Source : NASA Ames/A. S. Borlaff, P. M. Marcum, S. B. Howell

Astronomy facing mega-constellations…

Since the beginning of the deployment of the Starlink and OneWeb mega-constellations in 2019, astronomers have been trying to protect their discipline. These satellites, offering global high-speed internet access, create luminous streaks in optical observations by reflecting sunlight, and also disrupt radio astronomy via their communications and electronics leakage.

The consequences are real: contaminated images, false alarms for gamma-ray bursts or near-Earth asteroids, missed transient phenomena, etc. For the Vera Rubin Observatory, it is predicted that 20-80% of images will be affected1, an extreme case.

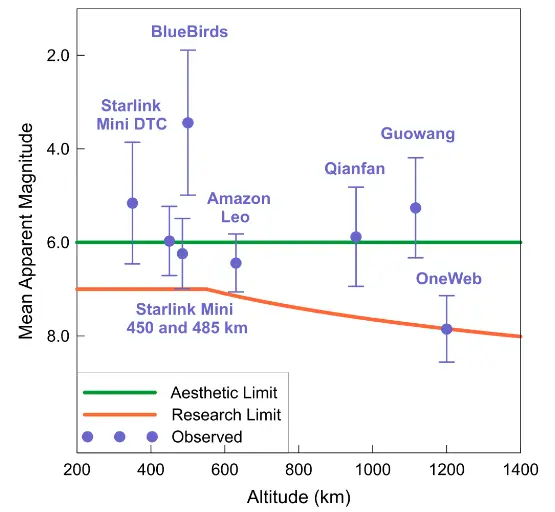

Despite some cooperative efforts, Starlink does not respect the visibility thresholds recommended by the International Astronomical Union (IAU)1,2,3. Furthermore, its new Version 3, designed for direct-to-device connectivity, requires larger satellites placed in lower orbits with more powerful antennas, creating more intense and less predictable disruptions2.

Above all, this is only the beginning. Starlink is not yet complete; three other mega-constellations are currently being deployed (Amazon Leo, Guowang, Qianfan), and other projects will follow, for a potential cumulative total of 560,000 satellites (compared to ~2,000 in orbit before 2019)4. No obligation forces these operators to cooperate: the first Qianfan/Guowang satellites already show extreme brightness2,5, while those of Amazon Leo perform no better than the early Starlinks despite being located at more problematic altitudes6.

… space debris

To this is added a structural problem: 130 million pieces of small debris from decades of space activity also reflect light, already increasing the diffuse brightness of the sky by about 10%, which is precisely the light pollution threshold set by the IAU7. This is an omnipresent disruption. The result: longer exposure times, increased costs, less science, and… a higher probability of contamination by satellites8.

… and launches and atmospheric reentries?

That is not all: other disruptions have also been reported, notably by the American Astronomical Society (AAS) in a 2024 statement9: dust from the return of satellites and rocket stages into the atmosphere which could increase its opacity, as well as high-altitude clouds and ionospheric holes caused by launches. These holes occur when rockets fire their engines 200 to 300 km above the Earth’s surface. While they have no known consequences for the environment, they cause a rapid recombination of ionized oxygen in the ionosphere, which excites molecules and causes them to emit energy as light, creating artificial auroras.

Disruptions even in orbit

No problem, some say: let’s send the telescopes into orbit10. But radio telescopes are too large, and for optical astronomy, an article published in Nature recently buried the idea4. Depending on the number of satellites deployed, 20-40% of Hubble images would be contaminated by at least one streak, and 80-97% for new space telescopes expected between 2025 and 2030, sometimes with nearly 100 streaks per image.

For example, the cover image of this article was not taken by an existing telescope: it is a simulation of an image from the ARRAKIHS mission (Analysis of Resolved Remnants of Accreted galaxies as a Key Instrument for Halo Surveys) currently being developed by the European Space Agency, which will not be launched until 2030.

A bad time for science

The rise of mega-constellations responds to powerful economic and geopolitical logics. In an era of post-truth, the decline of rational discourse, overt attacks on science, and the extreme simplification of public language—and in a world where 1/3 of humanity, 60% of Europeans, and 80% of Americans can no longer see the Milky Way10, will we be able to preserve the study of the Universe in the face of promises of global connectivity and the ambitions of states or oligarchs?

In this context, it is unfortunately not absurd to imagine that the understanding of the universe will be relegated to the background, sacrificed on the altar of global connectivity, competitiveness, and the inexorable march of a certain idea of progress.

Toward a slow and inexorable degradation?

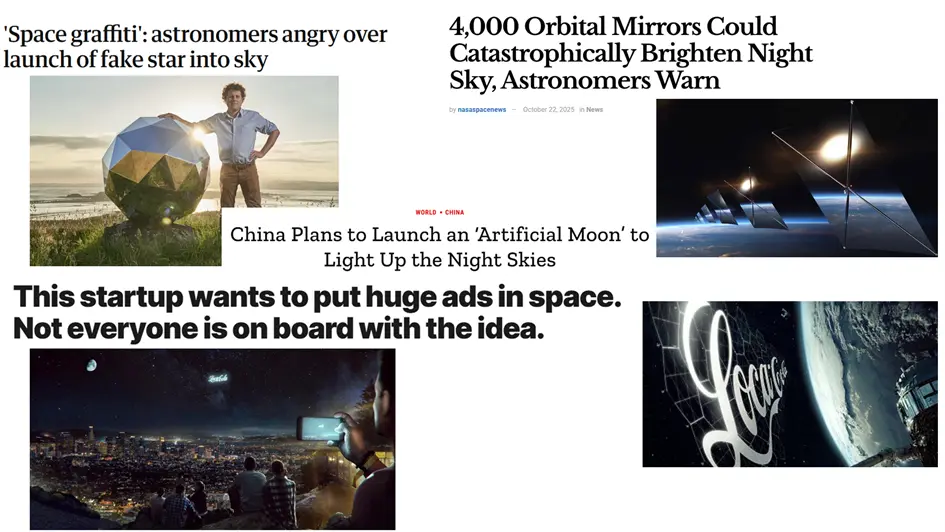

We risk witnessing a slow degradation, insidious and almost imperceptible year after year, but cumulatively devastating. A first constellation with “mitigated impact” calls for a second, then a third, thereby erasing their respective mitigation effects from the astronomers’ perspective. Then, as proposed, vast orbital infrastructures appear (solar stations, data centers…), followed by giant advertisements. —> See, for example, recent announcements from Google, Nvidia, Musk, and Bezos regarding space data centers and AI, Reflect Orbital regarding space mirrors, or other institutional actors (notably the UK) regarding orbital solar power stations; for advertisements, see projects by Avant Space.

Astronomy and astrophysics would then become progressively more complex and expensive, stifled by the planning of observations into ever-narrower windows and by the post-processing of increasingly contaminated images. A weakening caused not by brutal events, but by an addition of silent surrenders.

What can be done? The question of engagement

If I describe such a dark picture here, it is deliberate: as often said in the context of environmental or social crises, one must imagine the worst to better prevent it. For astronomers, this situation raises the question of engagement, marked, as in all struggles, by a fundamental tension:

- Collaboration with existing organizations and actors to transform them from within.

- Frontal opposition, for those who consider these structures to be the source of the problem and believe that collaborating amounts to legitimizing, or even consolidating, what they seek to combat.

In the case of mega-constellations, astronomers first had to understand the scale of the problem by characterizing light pollution and quantifying impacts. Thus, a large part of the effort was (and still is!) focused on diagnosis. Then, naturally, a compromise strategy emerged: formulating technical recommendations, requesting design changes, and negotiating the sharing of ephemeris data.

But this compromise raises a heavy question: by working to make these constellations “less harmful,” do we not legitimize their expansion? In a lukewarm compromise, a marginal adjustment, do we not allow a foot in the door that leads to progressive degradation as described in the previous scenario? Do we not thereby accept an appropriation of the night sky that can be considered fundamentally anti-democratic and carries unacceptable consequences for science and society?

Forced to collaborate?

It must be said that frontal opposition attempts have so far failed. The International Dark-Sky Association and other actors filed appeals against the FCC’s (Federal Communications Commission) authorization of Starlink Gen2, but in July 2024, the Federal Court of Appeals finally upheld the FCC’s decision11.

Thus, faced with a fait accompli — SpaceX already deploying Starlink — and given the power balance that does not favor astronomers, collaborating to minimize damage and “save what can be saved” was perhaps the pragmatic solution.

Small victories

But all is not lost. It is precisely to avoid an irreversible downward spiral that the AAS is now pleading for a total ban on orbital advertisements before the first project even sees the light of day12.

Just as with climate change, where every tenth of a degree and every ton of CO2 counts, here, every tenth of a magnitude in the brightness of a satellite, and every percentage of diffuse sky brightness preserved, is a small victory. Finally, there is always another form of resistance accessible especially to astronomers and astrophysicists. John Barentine reminds us of this in an article published in Nature Astronomy8, paraphrasing the Senegalese ecologist Baba Dioum:

We will conserve only what we value, value only what we know, and know only what we are taught.

Defending the night sky means understanding it, telling its story, showing it, and teaching it. Sharing the inestimable value of a starry sky free from all appropriation is giving everyone the profound desire to protect it, even when many of us can no longer see it.

References

1. Boley, A. C., Green, R., Rawls, M. L. & Eggl, S. IAU CPS Satellite Optical Brightness Recommendation: Rationale. Res. Notes AAS 9, 60 (2025).

2. Mallama, A., Cole, R. E., Harrington, S. & Respler, J. Brightness Characterization for Starlink Direct-to-Cell Satellites. Preprint at https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2407.03092 (2024).

3. Mallama, A. et al. Assessment of Brightness Mitigation Practices for Starlink Satellites. Preprint at http://arxiv.org/abs/2309.14152 (2023).

4. Borlaff, A. S., Marcum, P. M. & Howell, S. B. Satellite megaconstellations will threaten space-based astronomy. Nature 648, 51–57 (2025).

5. Mallama, A., Cole, R. E., Dorreman, B., Harrington, S. & James, N. Brightness of the Qianfan Satellites. Preprint at http://arxiv.org/abs/2409.20432 (2024).

6. Mallama, A. et al. Brightness Characterization and Modeling for Amazon Leo Satellites. Preprint at https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2601.07708 (2026).

7. Kocifaj, M., Kundracik, F., Barentine, J. C. & Bará, S. The proliferation of space objects is a rapidly increasing source of artificial night sky brightness. Mon. Not. R. Astron. Soc. Lett. 504, L40–L44 (2021).

8. Barentine, J. C. et al. Aggregate Effects of Proliferating LEO Objects and Implications for Astronomical Data Lost in the Noise. Preprint at https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2302.00769 (2023).

9. AAS. AAS Statement on the Atmospheric Impacts of Spacecraft Reentries and Launches. https://aas.org/about/governance/society-resolutions/atmospheric-impacts-spacecraft (2024).

10. Elon Musk sur X : https://x.com/elonmusk/status/ 1132897322457636864 (2019).

11. International Dark-Sky Association, Inc. v. Federal Communications Commission, No. 22-1337 (D.C. Cir. 2024). Justia Law https://law.justia.com/cases/federal/appellate-courts/cadc/22-1337/22-1337-2024-07-12.html.

12. AAS Statement on Obtrusive Space Advertising | American Astronomical Society. https://aas.org/about/governance/society-resolutions/space-advertising.