Bon Pote - Space tourism: it’s worse than you think

Why space tourism is likely the most extreme human activity in terms of climate and environmental inequality that an individual can legally engage in.

Source : Screenshot from a video on Katty Perry's Instagram account during her space flight.

The original version of this article was initially written for Bon Pote, an independent media raising awareness about climate change, and is accessible here.

—

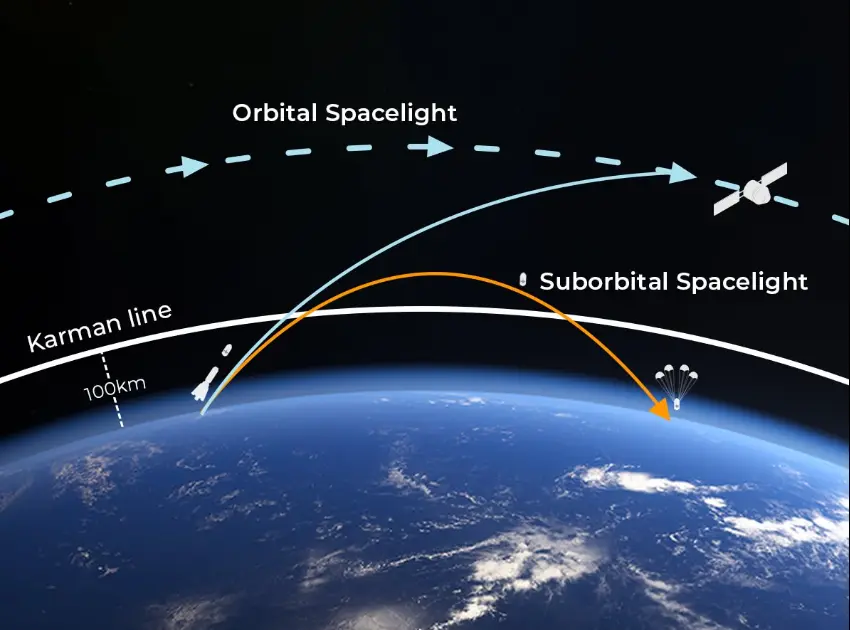

This Monday, April 14, Katy Perry took off with five other women aboard the capsule propelled by Blue Origin’s New Shepard rocket, Jeff Bezos’ company. After reaching an altitude of 106 km, slightly exceeding the Karman line conventionally defining the limit of space (100 km), the capsule landed without issue.

Stepping out of the capsule in front of the cameras, Katy gave a kiss to the Earth. The images were picked up by media outlets worldwide.

Unfortunately, we are starting to get used to this kind of spectacle. During the summer of 2021, we saw billionaires Richard Branson and Jeff Bezos jostle in a grotesque space race, each participating in the maiden flight of their respective company’s vehicle, Virgin Galactic and Blue Origin. As recently as March 31, Elon Musk’s SpaceX put a billionaire in orbit who made his fortune with cryptocurrencies, accompanied by three guests, a mission that went largely unnoticed compared to Katy’s.

As a reminder, as early as 2001, centi-millionaire Dennis Tito became the first space tourist by spending a few days on the International Space Station.

Nothing truly new, then, but now a real space tourism industry is being targeted with hundreds of annual flights hoped for, and, in the distance, grandiose goals: making space accessible to all for Richard Branson, financing the colonization of Mars and setting up point-to-point rocket travel for Elon Musk, or even transferring all of humanity into immense spaceships for Jeff Bezos.

But let’s go back to Katy’s flight: 10 minutes of thrills, 3 to 4 minutes of weightlessness… and for that, how many tons of CO2?

The climate impact of space tourism

To describe the carbon footprint of a space tourist, we will break down the life cycle of a rocket, putting aside the launch phase for now, meaning we first look only at ground-based activities.

The life cycle of a rocket until its launch pad

To have a rocket ready for takeoff, you must:

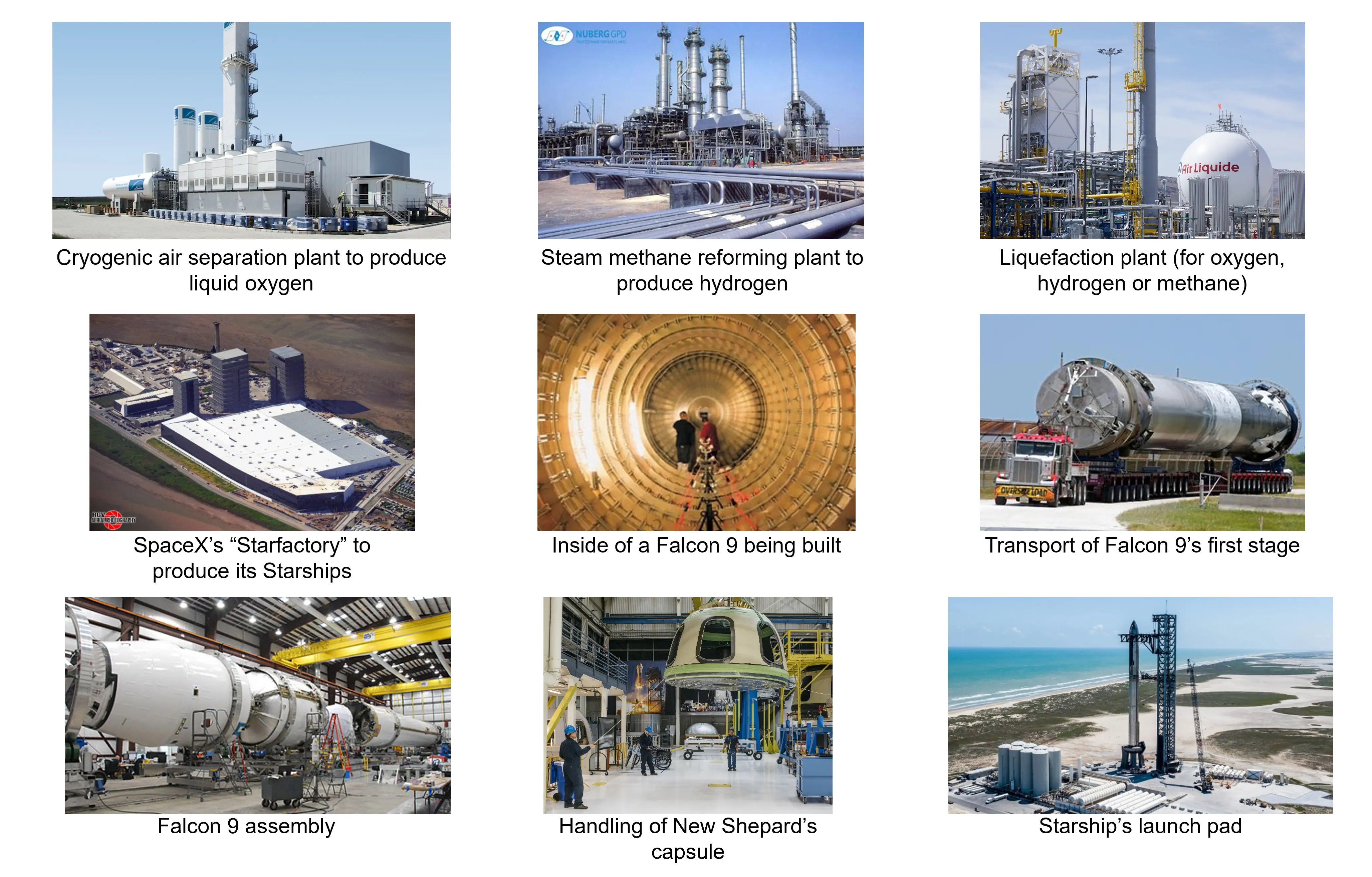

- Design it: This phase is generally negligible for traditional products but weighs much more for space systems, which are complex and rarely used.

- Manufacture it, which involves the extraction and transformation of raw materials, generally using advanced alloys and industrial processes.

- Transport and assemble the various components of the rocket, sometimes over thousands of kilometers.

- Produce the fuel AND the oxidizer: This is a major distinction of a rocket compared to a plane or a car; it must also carry the substance that burns with the fuel, usually liquefied oxygen. There are different types of fuel; let’s mention those relevant here:

- Kerosene, the most used in the space industry.

- Liquid hydrogen, used less and less (no, this is not low-carbon hydrogen, at least not yet—it is methane reforming, a very carbon-intensive process, that is used in the space industry).

- Liquid methane, recently adopted.

- Hydroxyl-terminated polybutadiene (HTPB), which is rarer.

- Store the fuel and oxidizer, sometimes at cryogenic temperatures (e.g., -253°C for hydrogen, -183°C for oxygen), while waiting for loading and takeoff.

- Refurbish and eventually replace components after landing in the case of rockets with reusable parts.

- Build, operate, and maintain numerous infrastructures: manufacturing and assembly plants, launch pads, control centers, etc.

Before takeoff, it’s already too much

Thus, even before taking off, one suspects that the footprint of a space tourist is already heavy, and we understand that reuse technology only offsets a fraction of this balance.

Only a few life cycle assessments (LCA) have been performed on rockets, and almost none are public. It is difficult to get precise information on the systems themselves due to significant confidentiality in the sector.

The exercise is made even more complex by the specificity of materials and processes, making conventional LCA databases unrepresentative and requiring specialized databases. Consequently, even in academia, estimations are difficult to make.

Impact of ground activities + launch CO2

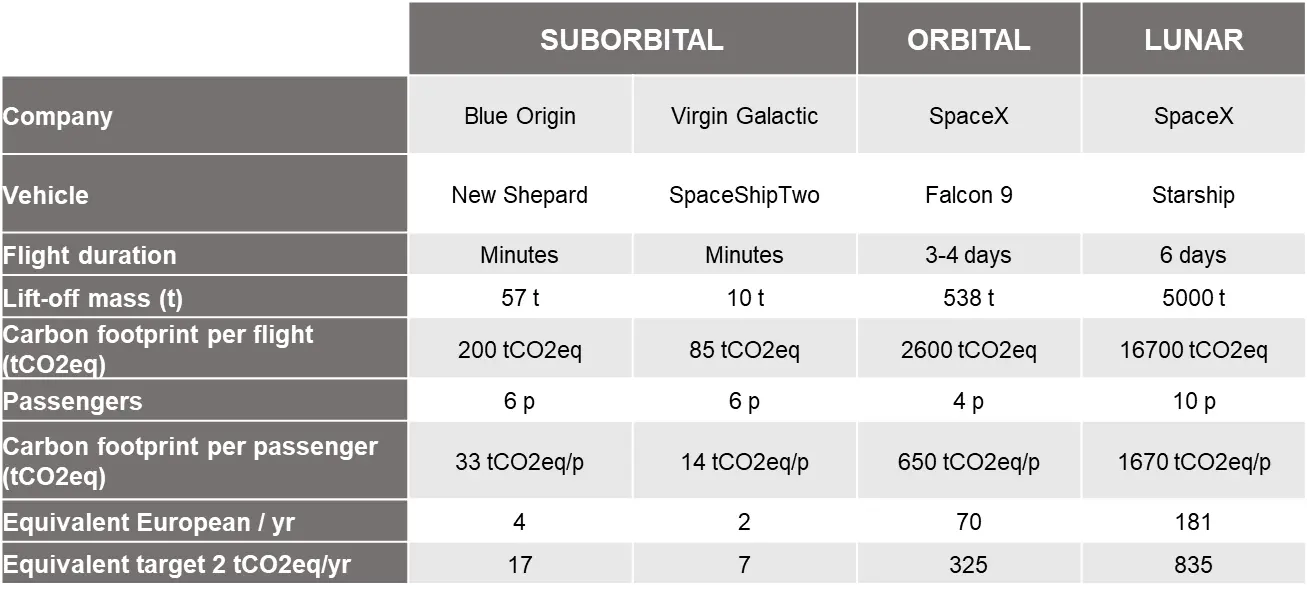

However, in a scientific publication1 conducted with two other researchers (presented here), we were able to use such a specialized database to estimate footprints per passenger for different space tourism flights, on a scope taking into account only the manufacture of the rocket and the production of fuels/oxidizers.

The launch phase was considered in an extremely simplified manner by considering only CO2 emissions due to uncertainties, lack of data, and the complexity of the problem—we will discuss this later.

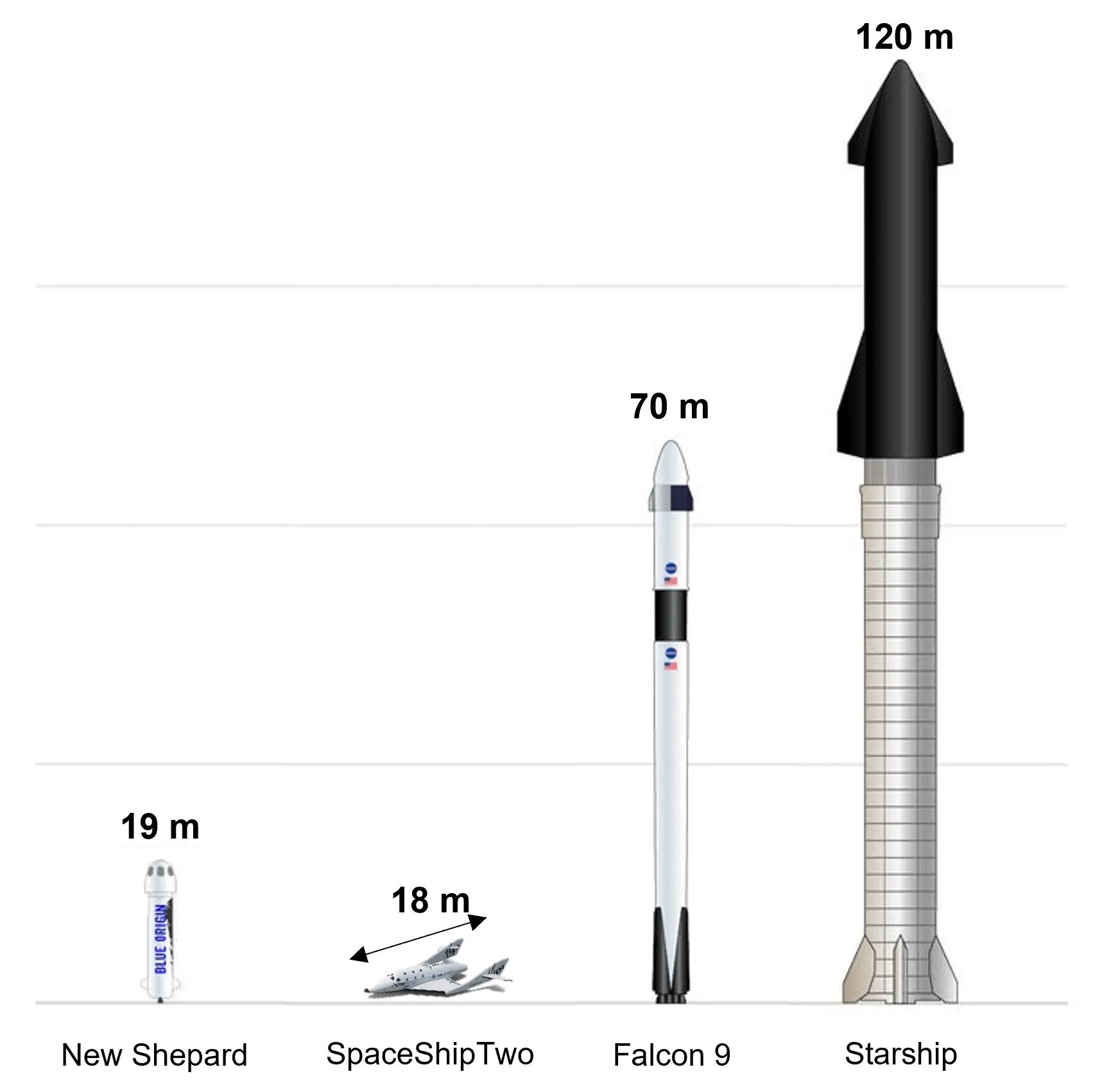

These estimations were made with assumptions of 20 to 30 reuses depending on the vehicle. Estimations covered the types of flights already mentioned (suborbital and orbital), but also a flight in lunar orbit based on the “DearMoon” mission planned by SpaceX with its Starship, which has since been cancelled.

NB: The SpaceShipTwo is somewhat unique; it is not a rocket. It is carried by a plane to altitude, and its solid propulsion engine only ignites once released, landing like a glider. The life cycle varies slightly: notably, the fuel of the carrier plane must be taken into account, which was done.

Result: even with a restricted scope, the footprints are already exorbitant:

- For a suborbital flight, the assessed carbon footprint is 85 to 200 tCO2eq/flight, or 14 to 33 tCO2eq/person. Katy Perry flew aboard New Shepard and therefore emitted at least 33 tCO2eq, all for a few minutes of weightlessness.

- Orbital flights require the use of energy quantities of a completely different order of magnitude, reflected in the size and mass of the vehicles used, and of course in the carbon footprint: 2600 tCO2eq/flight, or 650 tCO2eq/passenger.

- To go beyond, such as around the Moon, everything increases by another order of magnitude and we exceed a thousand tCO2eq/passenger…

To contextualize these footprints, we can compare them to that of an average European over a year (approx. 9 tCO2eq) or to the “target” of 2 tCO2eq/person/year to be reached to respect the Paris Agreement (even if it’s more complicated than that).

These values are, of course, only orders of magnitude given the high uncertainty of the data. But they are already very revealing, especially since they only constitute a lower bound.

First, because only part of the ground emissions was taken into account. In Katy Perry’s case, there would be other emission sources to add: her travel to the launch site, likely by private jet, and that of all the media who came to cover the event.

But above all, because the majority of the climate impact actually occurs during the launch phase.

Launch Impact

The main culprits: black carbon and water vapor

To understand how rockets affect the atmosphere during launch, we must first look at what they emit.

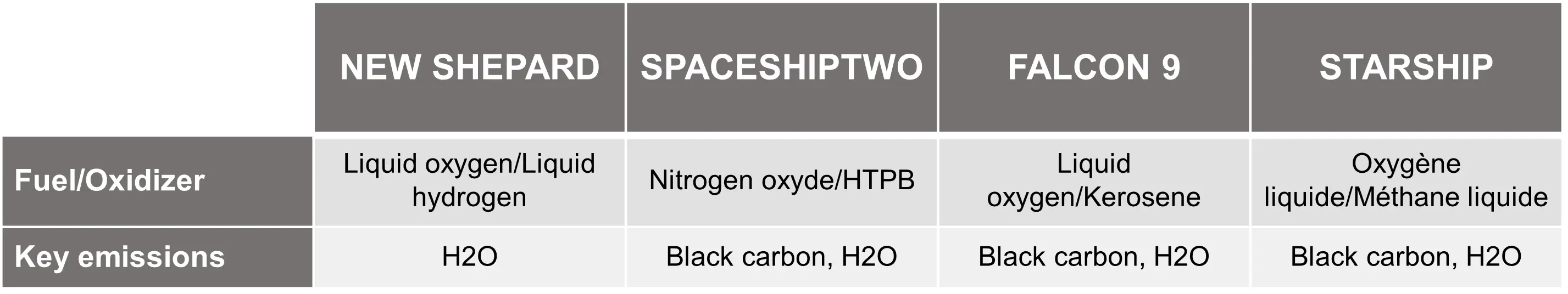

There is a great diversity of oxidizer/fuel combinations used in the industry: among the vehicles of interest here, each uses a different mix. The compounds emitted will therefore be very varied and of different natures: greenhouse gases, particles, and ozone-depleting radicals.

For simplicity, we will focus on two critical emissions for the climate impact of the rockets concerned: black carbon particles, and to a lesser extent water vapor. We set CO2 aside here because it has a completely negligible impact compared to the other two compounds.

In the upper atmosphere, multiplied effects

Emissions during the launch phase are particularly problematic due to two main factors.

The first is that rockets can emit particles in very large quantities, up to 1000x more black carbon than an aircraft engine per kg of fuel burned for the worst kerosene engines.

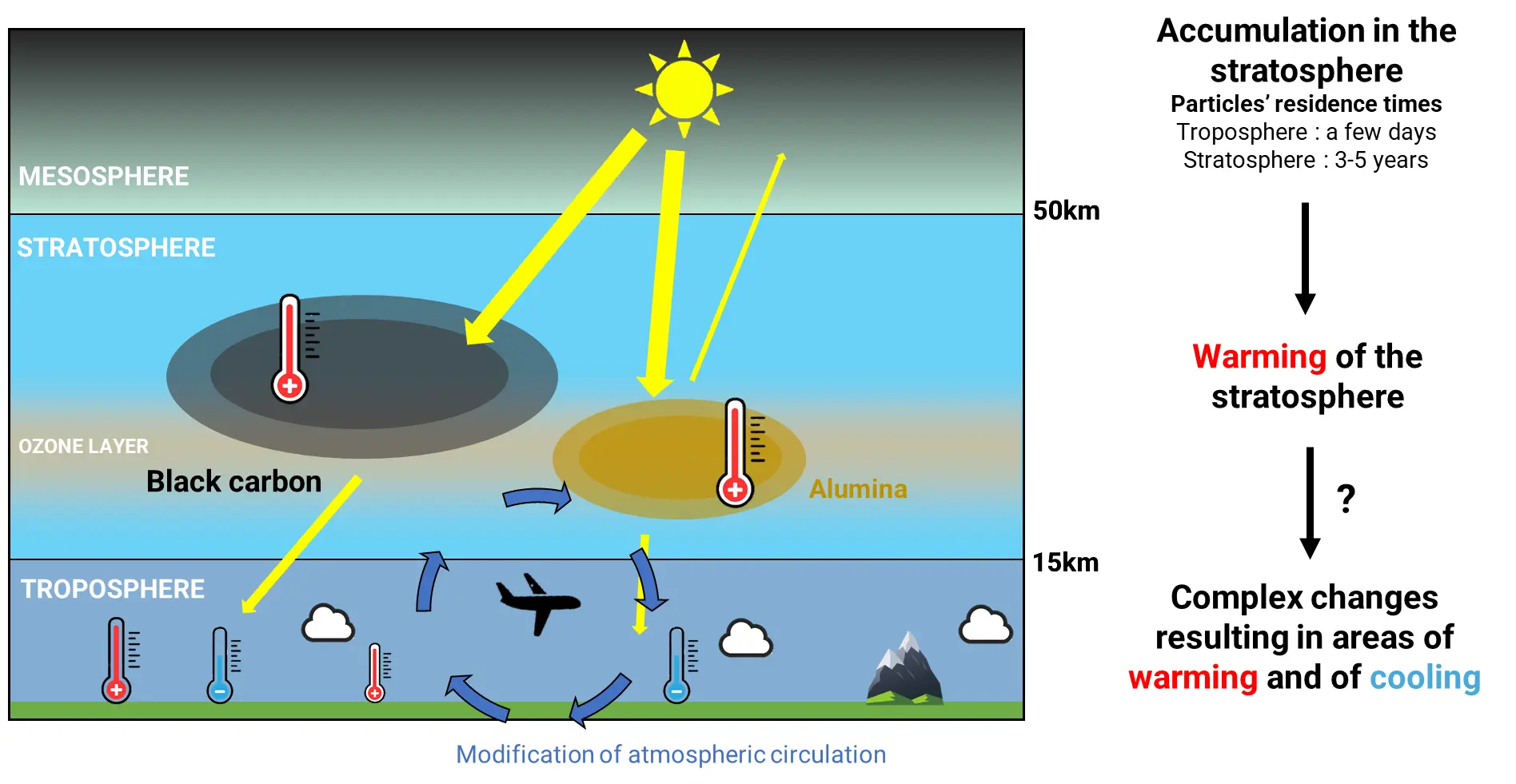

The second stems from the fact that during their ascent from ground to space, rockets emit in the upper layers of the atmosphere, unlike other human activities that emit only in its lowest layer, the troposphere (except aviation, which emits slightly in the stratosphere).

However, the effect of a substance on the climate or ozone varies according to its emission altitude. This is a well-identified phenomenon in the case of water vapor, a powerful greenhouse gas whose contribution to climate change is negligible when emitted at ground level2, but which plays a role in aviation’s climate impact3 and whose impact increases considerably if emitted in the stratosphere4. The oft-repeated argument that New Shepard has no climate impact because it only emits water vapor is therefore false.

For black carbon, it’s the same, but worse. Its residence time is a few days after emission in the troposphere, but a few years (3 to 5 years) after emission in the stratosphere5. It therefore has much more time to exert its power to disrupt the atmosphere’s radiative balance by absorbing light radiation, and its impact is thus decupled. For example, it has been estimated that a black carbon particle emitted by a rocket in the stratosphere is 500 times more effective at warming the atmosphere6 than the same particle emitted in the troposphere.

This warming of the stratosphere could result in complex changes leading to zones of local warming and cooling at the surface,7 but literature remains cautious: more simulations with better data are needed.

In terms of magnitude, the effect seems significant: the hundred or so rockets launched each year in the 2010s had a warming effect on the stratosphere estimated at about 4 to 16% of the warming effect of current aviation on the troposphere*. This figure is growing extremely rapidly (261 launches in 2024), mainly due to the deployment of Elon Musk’s Starlink satellite constellation. Yet, only a few studies are available and many uncertainties remain.

*One study5 estimated the radiative forcing of the 2013 rocket fleet at 16 mW/m2; another7 estimated that of the 2019 fleet at 4 mW/m2 (with a more limited scope). That of current aviation is approximately 100 mW/m23.

The two factors described above mean that even if the amount of fuel burned during a launch is small, its impact is multiplied. Thus, the climate impact of rockets—and therefore that of space tourists—is characterized by an overwhelming dominance of non-CO2 effects caused by launches.

But then, how much is that in tCO2eq?

Unfortunately, these effects cannot be rigorously expressed in conventional metrics such as Global Warming Potential (GWP) measured in tCO2eq, as this metric is not suitable for stratospheric emissions, especially of particles.

With this limitation in mind, one study5 still estimated an “analogous” carbon footprint for a passenger in a SpaceShipTwo-type flight at… several thousand tCO2eq, essentially due to black carbon.

This is two orders of magnitude higher than estimations for ground activities. For a vehicle not emitting black carbon but water vapor like New Shepard, the multiplier effect of high-altitude emissions is likely much lower, but it still exists. Katy’s footprint would therefore actually be much more severe.

More recently, a study estimated the impact of a heavily developed space tourism industry, with daily suborbital and weekly orbital flights, which corresponds to the plans of companies in the sector. After 3 years, its influence on atmospheric warming would be equivalent to one-tenth of the aviation sector, and it would have dangerous effects on the ozone layer.

Such a space tourism market is extremely speculative, but even simply in terms of footprint per passenger, the already poor balance for ground activities would then become disastrous.

Space tourism and climate justice

The few dozen tons of CO2 per passenger mentioned (when they are) in the press and social networks with each new flight seem quite ridiculous alongside the findings we have just established, even though they were already more than enough to spark indignation.

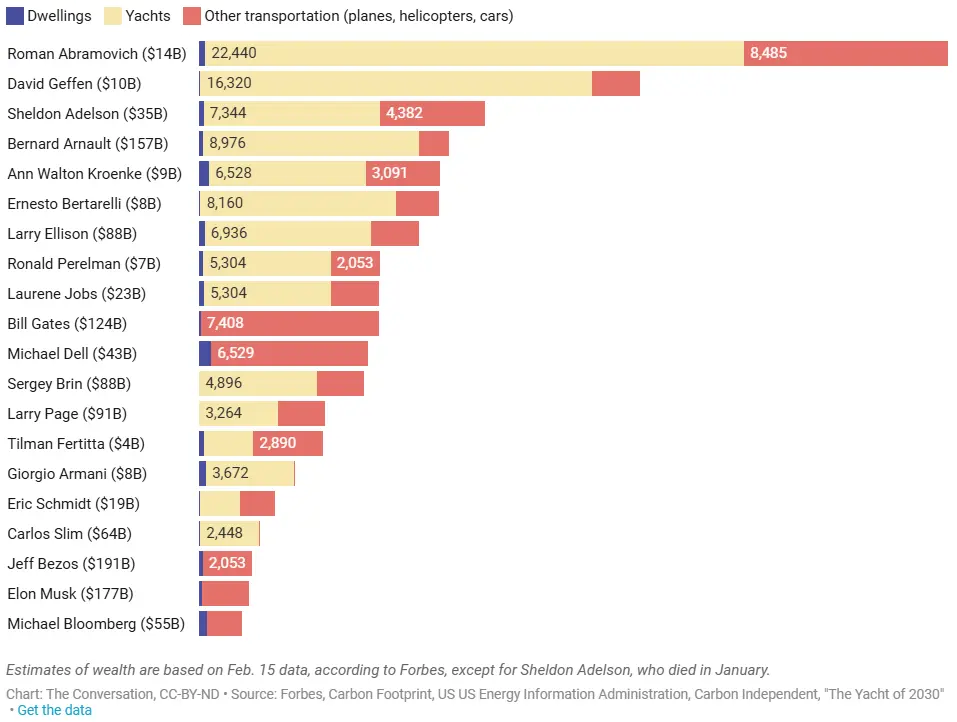

We are actually talking about an activity having effects on the atmosphere that have absolutely no equivalent, even among the ultra-luxury experiences that make up the environmental footprint of billionaires.

By using their yachts, helicopters, or private jets for an entire year, most billionaires generally do not exceed “a few thousand” tCO2eq and probably affect ozone very little. A score potentially pulverized in a few days or even a few minutes by our space tourists.

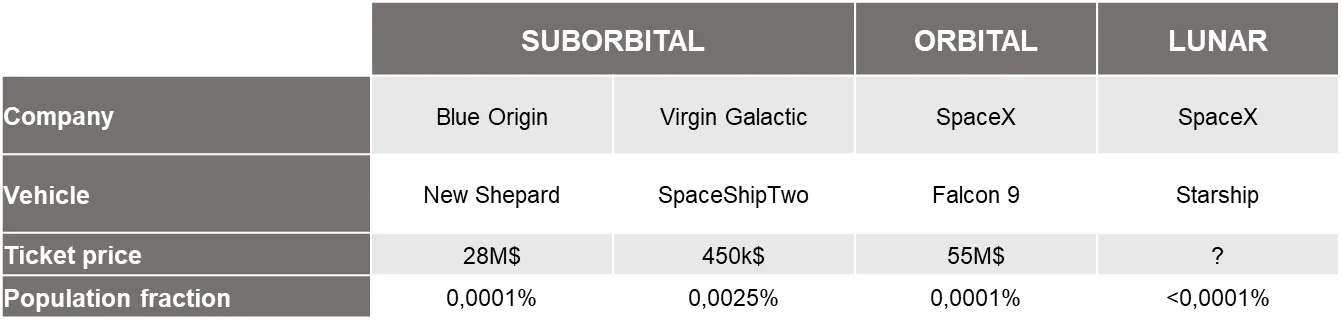

We suspect the “economic” part of the problem, but to write what follows in a scientific article, it had to be shown. Let’s do the exercise and look at the fraction of the population capable of investing in these experiences (obtained under the assumption of a maximum acceptable threshold of 10% of total wealth).

Potential clients are typically in the UHNWI (Ultra-High Net Worth Individual - top 0.003%) bracket or even the top few % of that bracket.

Space tourism therefore constitutes likely the most extreme human activity in terms of climate and environmental inequality that an individual can legally engage in.

This is serious because, beyond the impacts generated by the activity itself, it has concrete consequences on the fight against climate change and more generally against environmental problems.

The message sent by Katy Perry to her fans and the world is that an ultra-carbon-intensive, energy-intensive, and material-intensive lifestyle is an ultimate achievement to which one should aspire. And given the communication around this flight attempting to frame it as a feminist message, it specifically targets women, suggesting that this model is a symbol of empowerment.

More generally, not only do the wealthiest contribute disproportionately (notably) to greenhouse gas emissions, but they have an influence on emissions that extends far beyond through their powerful role as investors, citizens, senior officials, and particularly as role models. Consequently, their exemplarity is a determining factor8 for the broad acceptance of climate change mitigation policies.

Space tourism is unjustifiable

Changing dietary habits, heating less, cycling instead of driving, not flying to see an expatriate relative… then turning on the TV and seeing your favorite pop star go into space. In this context, how can one not be discouraged in their efforts?

The IPCC also highlights this point in the report9 of Working Group III of the AR6:

Individuals with high socio-economic status contribute disproportionately to higher emissions and have the highest potential for emissions reductions while maintaining a high quality of life.

High socio-economic status individuals are capable of reducing their GHG emissions by becoming role models for low-carbon lifestyles, investing in low-carbon businesses, and advocating for stringent climate policies.

In conclusion, space tourism has an exorbitant environmental footprint that is legitimate to find unacceptable, especially for an activity that falls under leisure.

Note that in terms of footprint, what is applicable to sending humans into space is obviously applicable to other things we send there: satellites, probes, telescopes. These systems provide various services—some, moreover, very useful for understanding and protecting the climate and whose benefits likely far outweigh the costs—and others more questionable in light of these challenges.

References

1. Miraux, L., Wilson, A. R. & Dominguez Calabuig, G. J. Environmental sustainability of future proposed space activities. Acta Astronaut. 200, 329–346 (2022).

2. Sherwood, S. C., Dixit, V. & Salomez, C. The global warming potential of near-surface emitted water vapour. Environ. Res. Lett. 13, 104006 (2018).

3. Lee, D. S. et al. The contribution of global aviation to anthropogenic climate forcing for 2000 to 2018. Atmos. Environ. 244, 117834 (2021).

4. Pletzer, J. F., Hauglustaine, D., Cohen, Y., Jöckel, P. & Grewe, V. The Climate Impact of Hypersonic Transport. EGUsphere 1–50 (2022) doi:10.5194/egusphere-2022-285.

5. Ross, M. N. & Sheaffer, P. M. Radiative forcing caused by rocket engine emissions. Earths Future 2, 177–196 (2014).

6. Ryan, R. G., Marais, E. A., Balhatchet, C. J. & Eastham, S. D. Impact of Rocket Launch and Space Debris Air Pollutant Emissions on Stratospheric Ozone and Global Climate. Earths Future 10, e2021EF002612 (2022).

7. Maloney, C. M., Portmann, R. W., Ross, M. N. & Rosenlof, K. H. The Climate and Ozone Impacts of Black Carbon Emissions From Global Rocket Launches. J. Geophys. Res. Atmospheres 127, e2021JD036373 (2022).

8. Nielsen, K. S., Nicholas, K. A., Creutzig, F., Dietz, T. & Stern, P. C. The role of high-socioeconomic-status people in locking in or rapidly reducing energy-driven greenhouse gas emissions. Nat. Energy 6, 1011–1016 (2021).

9. AR6 Climate Change 2022: Mitigation of Climate Change — IPCC. https://www.ipcc.ch/report/sixth-assessment-report-working-group-3/.